I ‘inherited’ a rustic copy of the book, An Autobiography, by Jawaharlal Nehru, the architect of modern India, or rather, found it desolately [considering that books have emotions] lying in my father’s old bookshelf, untouched for over a decade, as if pleading to be read.

This book aroused my interest the moment it came in my possession — for the highlights of the Indian freedom struggle always intrigued my fascination and the prospect of getting an insider’s perspective into this revolutionary epoch by glimpsing through the defining experiences of a prominent figure of the movement. It also kindled a burning desire in me to read the classy autobiography.

BEAUTY OF THE BOOK

Nehru’s book does not have that typical autobiographical monotone; it is a collection of personal reflections and holistic argumentations that will make you think and introspect on some of the crucial questions that need to be raised in the political, religious, economic and, for that matter, the personal domain of our lives.

It explicates the details of Nehru’s personal life, his upbringing, his education, his busy political career and the subsequent lack of time for his family, the choices and decisions he made at the forks of his life and his unique equations with his father, Motilal Nehru, and the voice and ‘messiah’ of India, Mahatma Gandhi.

The true beauty of the book lies in the eloquent expression of complex ideas and social issues that became the fundamental stepping stones in the Indian freedom struggle. Nehru delves into the controversies and conflicts within his mind and the members of the Congress Party with regard to the political route that had to be followed to achieve the end goal: freedom of thought, expression and distancing from imperial dominance and social hierarchy.

The book describes, in detail, Nehru’s emotions and conflicting thoughts from the instance when lathis were brutally thrashed on his quivering body to the agony that enveloped him when Gandhi arbitrarily chose to take some fundamental decisions without his or the party’s consultation.

Rabindranath Tagore, in his review of the book said, “Through all its details there runs a deep current of humanity which overpasses the tangles of facts and leads us to the person who is greater than his deeds and truer than his surroundings,” and it is this humane outlook and perceptive reasoning that is so abundantly present in this book that has a profound impact on its readers.

RELIGION & POLITICS

Nehru [November 14, 1889-May 27, 1964] rightly pointed out that, “No word perhaps in any language is more likely to be interpreted in different ways by different people as the word ‘religion.’ Probably to no two persons will the same complex of ideas and images arise on hearing or reading this word.” History stands as evidence for the perfunctory and misguided use of this word, which has invoked, and still continues to invoke, communal tensions and rivalry among different ‘religious’ groups.

However, in Nehruvian terms, religion lays stress on the inner development of the individual and the evolution of their consciousness, which powerfully influences the outer environment. Gandhi also emphasised on the moral and ethical aspect of ‘religion.’ His strong belief in the synchronous nature of religion and politics is reflected in the statement: “No man can live without religion. There are some who in their egotism of their reason declare that they have nothing to do with religion. But, that is like a man saying that he breathes, but that he has no nose.” The lack of mutual comprehension among diverse members of society on the exact meaning of the word ‘religion’ has created confusion — whether religion and politics have to necessarily co-exist.

Nehru believed in the ideals of democracy based on secularism. He strongly opposed the constant use of the word ‘religion’ in politics, while Gandhi stood as a staunch advocate for the use of religion in the political discourse as he felt that it was the most suitable way to reach out to the masses. As a result, the duo would often clash and have conflicting views — this can be observed in the book.

Today, the perilous politics of religion has exacerbated the political situation of the country. The political actors at all fronts have interpreted ‘religion’ in a different light as opposed to what Nehru and Gandhi propagated during the glorious years of our freedom struggle. This has given rise to innumerable cases of prejudice, violence and riots across the country.

Nehru’s book makes one ponder over the disturbed reality we are living in and the need to adopt a more secularist approach in ‘real terms,’ and not just on paper, or through ‘empty rhetoric.’

NEHRU-GANDHI RELATIONSHIP

Nehru was a fond admirer of Gandhi’s eloquence and alacrity. Nehru writes, “His calm, deep eyes would hold one and gently probe into the depths; his voice, clear and limpid, would purr its way into the heart and evoke an emotional response. […] Having found an inner peace, he radiated it to others and marched through life’s torturous ways with firm and undaunted step.” Nehru and Gandhi, in general, had a cordial relationship based on mutual respect and admiration. Gandhi would often write to Nehru when the latter would be in prison and inform him about current happenings. Gandhi would also regularly visit Nehru’s family. He became especially sensitive towards Nehru after Motilal’s death.

Yet, no relationship is perfect: Gandhi would firmly refuse Congress presidentship whenever it was offered to him, even when it would be a dire need of the hour. ‘Congress President’ was just a title, but Gandhi was much beyond it in stature. He was always considered as ‘over-the-president’ because he was a ‘magician’; he knew how to sway the audience and his plans always worked. It was Gandhi’s constant refusal to take the title that paved the way for Nehru to be elected as Congress President. Nehru was considered as the ‘next option,’ or the ‘second resort,’ which Nehru particularly disliked, or abhorred, for he had also made immense contributions to the Party and was dedicated to its cause.

Moreover, when Gandhi decided to go forward with the ‘Harijan Movement,’ Nehru was taken aback. Nehru believed that focusing on a ‘less significant issue’ would blur the larger vision. In fact, the Civil Disobedience Movement suffered a great deal and almost came to a halt because most of the party resources were being allocated towards the ‘Harijan Movement.’ Nehru felt that since Gandhi connected with the masses so well and empathised with their sufferings, he would always be more focused towards localised issues and would delay the attainment of the end goal. These factors created a certain strain in Nehru’s mind for Gandhi’s attitude in politics, but it never interfered with the especial bond they had developed over the years.

SATYAGRAHA: WAY FORWARD

Gandhi in his famous article, The Doctrine of the Sword, wrote, “Non-violence in its dynamic condition means constant suffering. It does not mean meek submission to the will of the evil-doer, but it means putting of one’s whole soul against the will of the tyrant.” Nehru acknowledges the method of non-violence and Satyagraha in his book: “Non-violence was the moral equivalent of war and of all violent struggle. It was not merely an ethical alternative, but it was effective also.”

But when the Non-Violence Movement was called off after the disturbing Chauri Chaura incident, the members of the Congress, including Nehru, felt that if Gandhi’s reason for the suspension of civil resistance was correct then their opponents would purposely create circumstances which would result in the abandoning of the struggle. The question was, “If the non-violent method of struggle could not function because of inevitable acts of violence, then was it the ideal method under all circumstances.”

Maybe, it was not. But, they all were certain that the alternative was much more dangerous. Nehru writes, “There is little doubt that if the movement had continued there would have been growing sporadic violence in many places. This would have been crushed by the government in a bloody manner and a reign of terror would be established which would have thoroughly demoralised the people.”

Nehru knew, and realised, that Satyagraha was the most appropriate means to an end, and that terrorism and large-scale violence would not flourish in the long run.

INSPIRATION TO READERS

Jawaharlal Nehru wrote his autobiography between the years 1934 and 1935 when he was in prison. In his years of solitude, he was able to ruminate on the key events of his life and their significance in the Indian freedom struggle, thereby crafting an extraordinarily written piece — a work of lasting value that gives us deep insights into this marvelous period in history that shaped the ideals of modern India.

In a postscript written five years, after the publication of the book, Nehru remarked, “As I glance through my book again, I feel almost as if some other person had written a story of long ago.” The book, which encompasses over 650 pages, is perceptibly a long read, but readers would feel as if they are a part of Nehru’s quest in the political [re]awakening of our nation and in his joie de vivre, and that, by itself, is worth its weight in pure gold.

Nehru’s autobiography is sure to enlighten, inspire and also enliven one’s mind — for today and tomorrow.

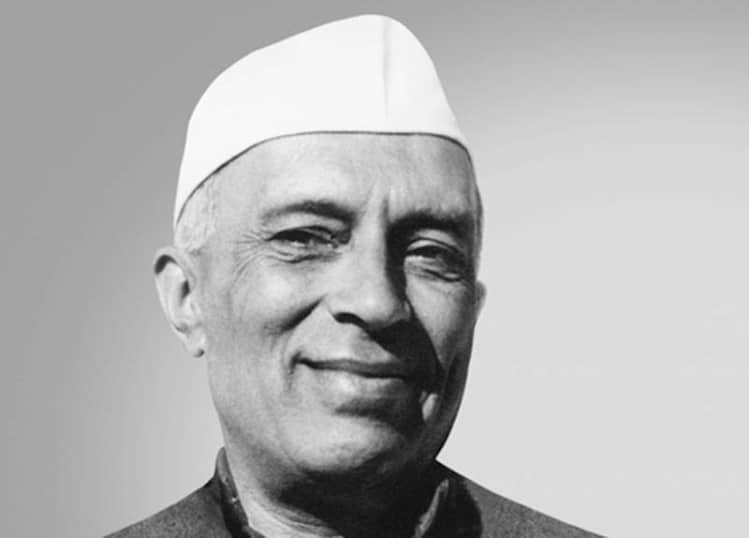

[Jawaharlal Nehru: Photo, Courtesy: The Free Press Journal]